EPISODE:

VINDICIÆ GEOLOGICÆ, RELIQUIÆ DILUVIANÆ, 1820-23

<<-- Episodes Listing

“Y a-t-il eu un temps où le globe ait été entièrement inondé ? Cela est

physiquement impossible.” ("Inondation," Voltaire, 1764)

“[A] universal deluge at no very remote period is proved on grounds so decisive

and incontrovertible, that, has we never heard of such as event from Scripture .

. . Geology itself must have called in the assistance of some such catastrophe,

to explain the phenomena of diluvian action which are universally presented to

us, and which are unintelligible without recourse to a deluge exerting it

ravages at a period not more ancient than that announced in the Book of Genesis”

(Buckland, 1820)

In

1812, William Buckland (1784-1856) was appointed as reader (“professor”)

of mineralogy at Oxford University. At that time, Oxford was a bastion of the

Church of England establishment and academicians at Oxford had to be ordained

ministers in that Church. In 1818 he petitioned successfully to have geology

established as a discipline of study and in 1819, to inaugurate his new position

as Reader of Mineralogy and Geology, he gave a lecture on the topic of “the

connexion of geology with religion.”

In

1812, William Buckland (1784-1856) was appointed as reader (“professor”)

of mineralogy at Oxford University. At that time, Oxford was a bastion of the

Church of England establishment and academicians at Oxford had to be ordained

ministers in that Church. In 1818 he petitioned successfully to have geology

established as a discipline of study and in 1819, to inaugurate his new position

as Reader of Mineralogy and Geology, he gave a lecture on the topic of “the

connexion of geology with religion.”

In his

lecture he was careful to show that geology, like other sciences, was entirely

compatible with conventional religion in various ways. Of particular relevance

here was his claim that there was geological evidence of events mentioned in the

Bible. While he did not shy away from asserting his belief that Earth was

extremely old – which was the conventional view among scholars by then – he

emphasized that “[A] universal deluge at no very remote period is proved on

grounds so decisive and incontrovertible, that, has we never heard of such as

event from Scripture . . . Geology itself must have called in the assistance of

some such catastrophe, to explain the phenomena of diluvian action which are

universally presented to us, and which are unintelligible without recourse to a

deluge exerting it ravages at a period not more ancient than that announced in

the Book of Genesis.” At the time, most geologists agreed that a major break

with the past had occurred relatively recently, and most believed that it was

aqueous in nature, but Buckland was virtually alone at this late date in

equating it specifically with the Mosaic Deluge.

The evidence of a catastrophic deluge he refers to here are: the presence of

loose, often unsorted deposits (“diluvium”) overlying the solid bedrock; the

carving of various topographic features, including valleys (“vast chasms or

gorges, the production of which is not referable to any causes now in action,

and which indicate a series of different operations conducted at an ancient

period of time”); and the geologic record of recent extinctions that were by

then well established by the work of Cuvier and others to have occurred at the

end of the Tertiary Period. The fact that human remains had not, as yet, been

found in these deposits, was ascribed to the fact that humans were still limited

to the Middle East at the time of the flood.

The

lecture was published the next year (1820) under the title of Vindiciae

Geologicae .

Buckland

climbed into the top echelon of Europe's geo-historians with his work on recent

fossil sites in England. This work complemented that of the great French

naturalist Georges Cuvier and Buckland received the Royal Society of

London's prestigious Copley Medal (left) for part of it.

Buckland

climbed into the top echelon of Europe's geo-historians with his work on recent

fossil sites in England. This work complemented that of the great French

naturalist Georges Cuvier and Buckland received the Royal Society of

London's prestigious Copley Medal (left) for part of it.

Buckland's book Reliquiae Diluvianae (“Traces of the Flood”) summarized

his own research and reviewed that of several other geologists. Its focus was

twofold: to establish "that there has been a recent and general inundation of

the globe," and to establish the nature of the native fauna at the time of the

debacle (p.47).

Upon

reviewing: the contents of various caves in England and Wales and in Germany,

landforms such as those described by James Hall in the Edinburgh region and the

erratics described by de Saussure, and the nature of deposits sitting atop the

bedrock through much of northern Europe (“diluvial loam and gravel”), he

concluded: that there was “the strongest evidence of an universal deluge.”

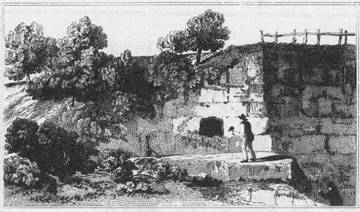

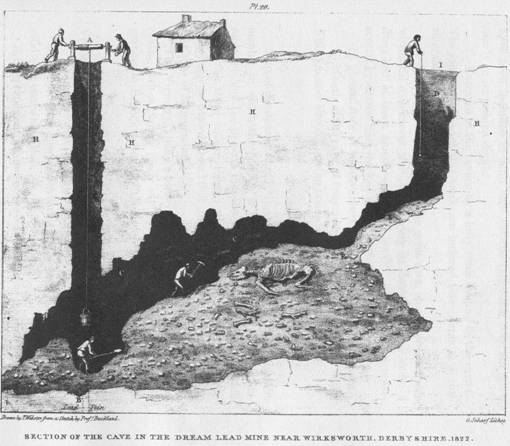

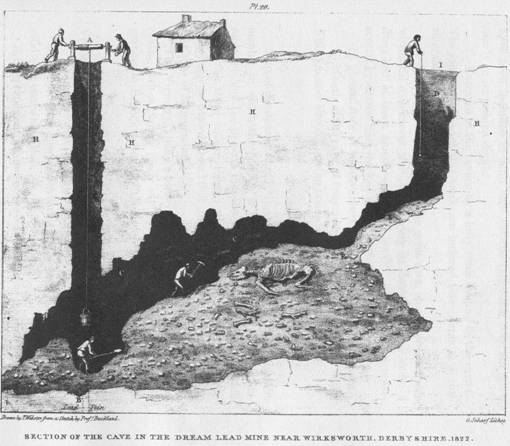

Kirkdale Cave (Yorkshire):

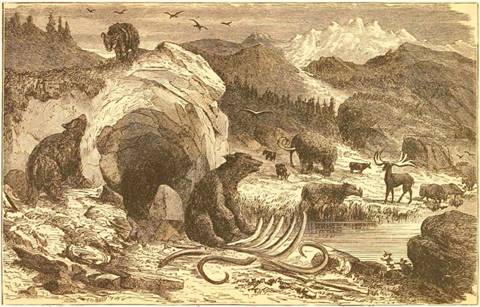

Here,

Buckland found evidence of a hyenas' den. This was the work for which he

received the Copley Medal in 1822. The bones in this and similar caves in northern

Europe contained provided evidence of life prior “to the last great convulsion

that has affected [the planet’s] surface.” Buckland equated this “convulsion”

with the “recent and transient inundation” described by Georges Cuvier in his

researches on the continent. Generally these were species not found today in

northern Europe (such as hyena, tiger, elephant [mammoth], rhinoceros, and

hippopotamus). “So completely has the violence of that tremendous convulsion

destroyed and remodeled the form of the antediluvian surface, that it is only in

caverns that have been protected from its ravages that we may hope to find

undisturbed evidence of events in the period immediately preceding it” (p.42).

Buckland refused to address the cause of the inundation: in fact, “the

discoveries of modern geology . . . have not yet shown by what physical cause it

was produced" (p.225-226). But he did note that there did appear to have been a

sudden change in climate at the time of the inundation, as evidenced by the

frozen elephant [mammoth] recently found in Siberia and described by Cuvier and

others.

Superficial deposits, erratics, landforms:

“Diluvium [is] . . . extensive and general deposits of superficial loam and

gravel which appear to have been produced by the last great convulsion that has

affected our planet” (p.2).

“The

[diluvium] itself possesses no character by which it is easy to ascertain the

source [the process] from which it has been derived . . . The catastrophe

producing this gravel appears to have been the last event that has operated

generally to modify the surface of the earth” (p.191).

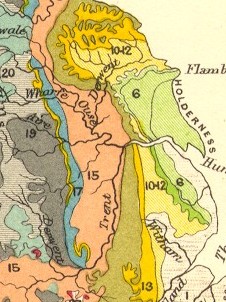

Buckland described these materials as being widely distributed to the north of

the River Thames.

Some

rocks clearly had come from Norway, implicating “a violent rush of waters from

the north” (p.198). Buckland accepted that flood waters could move erratics of

considerable size.

Buckland enthusiastically endorsed the work of Sir James Hall in the Edinburgh

region concerning landforms and “dressings” on rocks (scratches, gougings) that

appeared to be the result of a flood. Regarding erratics in the Jura Mountains

of Switzerland (such as Pierre a Bot), he accepted evidence of inundation to the

highest altitudes in the Andes and Himalayas, quoting Genesis: “all the high

hills and mountains under the whole heavens were covered” (p.223)[Genesis 7:19].

At this stage in his career, he equated this “recent and general inundation of

the globe” with the Genesis Flood. Although older students of Earth’s history

such as Linnaeus and Voltaire might have been skeptical (“Y a-t-il eu un

temps ou le globe a ete entierement inonde? Cela est physiquement impossible” -

Voltaire), unlike he and Cuvier, their opinions were not informed by the

researches of “modern geology,” according to Buckland (p.225). However, Hall had

clearly implied than there had been more than one wave at different places and

times throughout Earth's history, and most British geologists at the time, while

they accepted that there had been a relatively recent deluge, were non-committal

on its identification as the Noachian Flood.

Valleys:

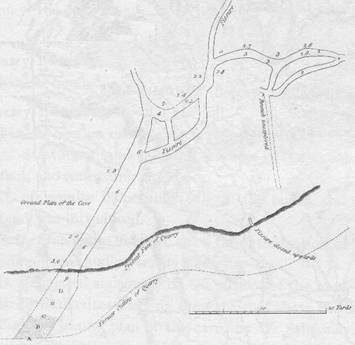

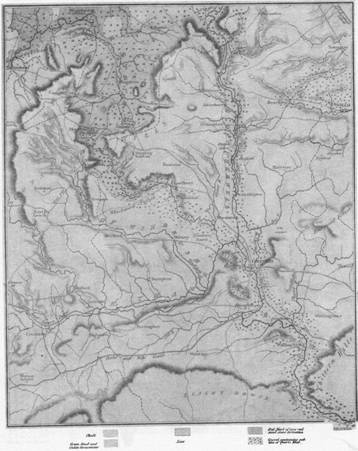

There

was an on-going debate concerning the origin of valleys at this time. Buckland

ascribed valleys to the “retiring action” of the “diluvial waters.” Buckland

found it “quite impossible the [erosion of the valleys] could have been produced

in any conceivable duration of years by rivers that now flow in them" (p.237).

He

cited two specific instances:

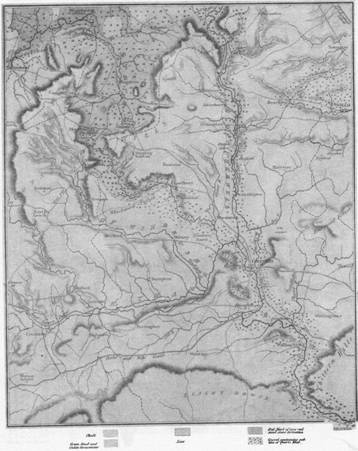

He

believed: Kirkdale cave had existed on the shore of a lake in the Vale of

Pickering: this lake then drained as flood waters cut the present gorge of the

Derwent River through the Howardian Hills and chalk escarpment to the south

(p.43-44). (The Derwent drains away from the coast although it originates within

a few miles of the coast.)

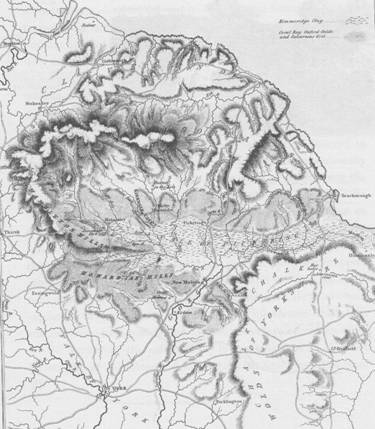

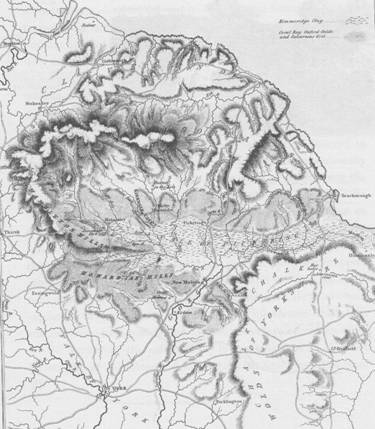

The

valleys of the Cherwell and Evenlode Rivers breach the Cotswolds escarpment

north of Oxford, and both valleys contain a trail of quartz pebbles (also

located on uplands) that originate in the Vale of Avon lowland to the north

(p.249 et seq.).

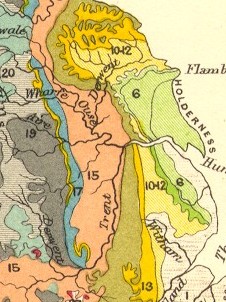

Diluvial thinking, overall:

Physical and biological evidence pointed to a relatively recent, dramatic event

in Earth's history, the evidence for which was very fresh indeed. A global

deluge (or a series of regional deluges) appeared to be the correct kind of

process (in fact the only kind known) believed capable of effecting such

dramatic changes across wide areas of Earth's surface: it fit well within the

thinking of the day.

QUESTIONS:

- Buckland refused to address the cause of the inundation: “the discoveries of

modern geology . . . have not yet shown by what physical cause it was

produced" and admitted that “The [diluvium] itself possesses no character by

which it is easy to ascertain the source [the process] from which it has

been derived.” If the Diluvium was laid down by a flood, how important is it

to know source of water or the mechanism of flooding? Can a process we know

nothing of, be a "scientific" explanation?

- Some rocks clearly had come from Norway, implicating “a violent rush of

waters from the north.” How important might the direction of apparent motion

be in deciding the origin of the features he considered?

|

The Vale of Pickering, drained by the south-flowing Derwent River.

|

The escarpment of the Cotswold Hills north of Oxford, breached by

the Evenlode (W) and Cherwell (E) Rivers.

|

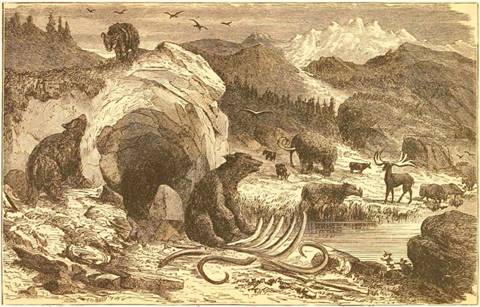

“Ideal View of the Quaternary Epoch – Europe

(Figuier, 1863, p.316)

REFERENCES

Buckland, W. 1820 Vindiciæ geologicæ; or The connexion of geology with religion

explained, in an inaugural lecture delivered before University of Oxford, May

15, 1819, on the endowment of readership in geology (William Buckland Publisher,

Oxford)

http://ships.umn.edu/glaciers/Buckland/Vindiciae

Geologicae William Buckland.pdf

Buckland, W, 1823 Reliquiae Diluvianae: or, observations on the organic remains

contained in caves, fissures, and diluvial gravel, and on other geological

phenomena, attesting the action of an universal deluge (John Murray, London)

http://books.google.com/books?id=VsoQAAAAIAAJ

Figuier,

L. 1863 The world before the deluge (Cassel, Petter, Galpin & Co, London)

http://imgbase-scd-ulp.u-strasbg.fr/displayimage.php?album=963&pos=3

http://www.geology.19thcenturyscience.org/books/1872-Figuier-BeforeFlood/htm/doc.html

<<-- Episodes Listing

In

1812, William Buckland (1784-1856) was appointed as reader (“professor”)

of mineralogy at Oxford University. At that time, Oxford was a bastion of the

Church of England establishment and academicians at Oxford had to be ordained

ministers in that Church. In 1818 he petitioned successfully to have geology

established as a discipline of study and in 1819, to inaugurate his new position

as Reader of Mineralogy and Geology, he gave a lecture on the topic of “the

connexion of geology with religion.”

In

1812, William Buckland (1784-1856) was appointed as reader (“professor”)

of mineralogy at Oxford University. At that time, Oxford was a bastion of the

Church of England establishment and academicians at Oxford had to be ordained

ministers in that Church. In 1818 he petitioned successfully to have geology

established as a discipline of study and in 1819, to inaugurate his new position

as Reader of Mineralogy and Geology, he gave a lecture on the topic of “the

connexion of geology with religion.”