THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GLACIAL THEORY,

1800-1870

1. INTRODUCTION

<<-- Project Home |

2. GoogleEarth Tour -->>

“. . . numberless

phenomena have been already ascertained, which, without the admission of a

recent and universal Deluge, it seems not easy, nay, utterly impossible to

explain” (Buckland, 1820, p.38).

"Others have referred to the deluge,—a convenient agent

in which they find a simple solution of every difficult problem exhibited by

alluvial phenomena" (Lyell 1833, p.148)

“If this [glacial] theory

be correct, and the facility with which it explains so many phenomena which have

hitherto been deemed inexplicable, induces me to believe that it is; then it

must follow that there has been . . . a fall of temperature far below that

which prevails in our days” (Agassiz, 1837, p.377).

![[Deluge+of+the+North+of+Europe.jpg]](INTRODUCTION_files/image002.jpg)

“The Deluge of the north of Europe” (Figuier, L. 1863 p.321)

(Note the ice-bergs transporting boulders; trees give relative scale)

http://imgbase-scd-ulp.u-strasbg.fr/displayimage.php?album=963&pos=3

http://www.geology.19thcenturyscience.org/books/1872-Figuier-BeforeFlood/htm/doc.html

“The period of the Diluvium, or Ice Age, with a glacier invading the land”

(Unger 1851)

(USGS Photographic library:

http://libraryphoto.cr.usgs.gov/htmllib/btch528/btch528j/btch528z/lwt01322.jpg

)

This case study in the nature and history of science traces the

development of the glacial theory and the manner in which it came to be

accepted.

Ultimately, the glacial theory

made sense of a great many features in the landscape of northern Europe

(and elsewhere), and a few other things besides. Of course before the glacial

theory was formulated or accepted, scientists made sense of these features in

other ways that fitted within the frame of their existing ideas about the

physical landscape, climate, and the workings of the planet in general

(Berger 2007 outlines pre-scientific ideas concerning many of the features

discussed here – something outside the scope of this study).

This study examines how a new

explanatory framework came to be established. It examines the ways in which

naturalists understood landscapes in northern Europe in the early 1800s and how

this understanding changed, in part, as the new idea of continental glaciation

emerged through the period 1800 to 1870.

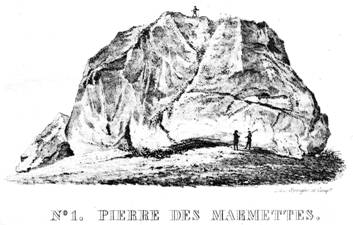

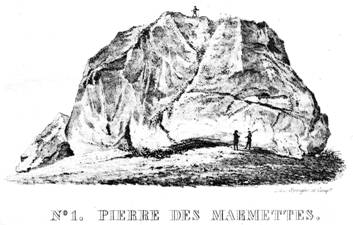

One landscape feature that had

long puzzled people all across northern Europe was the phenomenon of “erratics”

(Fr. erratiques – “wanderers” Ger. findlingen – “foundlings”).

The most spectacular erratics are massive, isolated boulders that geologists

quickly recognized were not derived from the local bedrock: therefore, evidently

they had been transported to their present location from a source often many

miles distant and often across valleys or seas. The question was: how did they

move to their present location?

The massive Pierre des Marmettes erratic, Monthey, Switzerland.

Note size in relation to people.

(Charpentier, 1841)

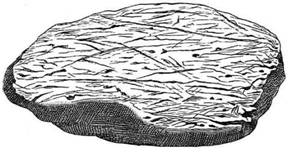

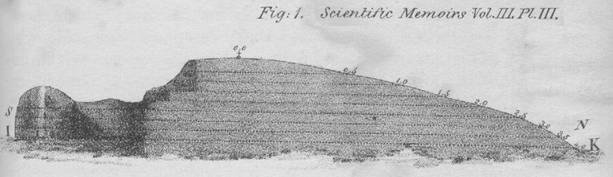

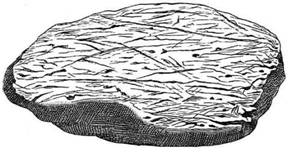

Other features that geologists

believed came from the time of the erratics included striated (scratched) and

grooved bedrock, and roches moutonnees (“sheep rocks”) – rounded bedrock knobs

that were smooth, often striated, on one side and ragged on the other: in any

given area, it was always the same sides that were striated or ragged.

Striated rock (~1/8 scale), Wesserling, Thur valley, Vosges region of France

(Collomb, 1847)

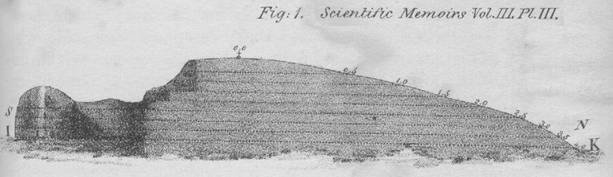

Roche moutonnee, Fa(h)lun area, SE Sweden: scale in feet (Sefstrom, 1836)

There was also the puzzle of the

loose sands and gravels and unsorted clays (“boulder clay” or “till”) that

covered much of the bedrock over northern Europe, and which contained erratics

of all sizes, down to the size of the smallest pebble. This “diluvium” or

“drift,” as it was termed, was clearly not river alluvium (it was found on

divides as well as in valleys and often formed ridges – moraines – that were

quite distinct from levees): but what was its origin? “Boulders” and “clay” was

an unusual mix of materials – all known agents of transportation and deposition

tend to sort (or winnow) material by size.

Large erratic in boulder within “drift” over bedrock, Baltic shore, Saaremaa,

Estonia

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RaisedBeachSaaremaa.JPG

Whatever the answer(s) to these

puzzles, they had to cohere with other ideas geologists held about Earth. For

example, the origin of valleys was actively debated in the 1700s and much of the

1800s: some believed that valleys were the result of river erosion acting over a

long period of time; others – the majority during much of the first half of the

century – reasoned that larger valleys and those valleys that cut across

regional rock structure, in particular, were formed by a major flood or some

such catastrophe in the recent past. This flood had perhaps also laid down the

layer of loose sediment found over much of the solid bedrock. Those who accepted

a flood mechanism possibly also had a mechanism to transport erratics, if it

could be shown that water could move such large objects.

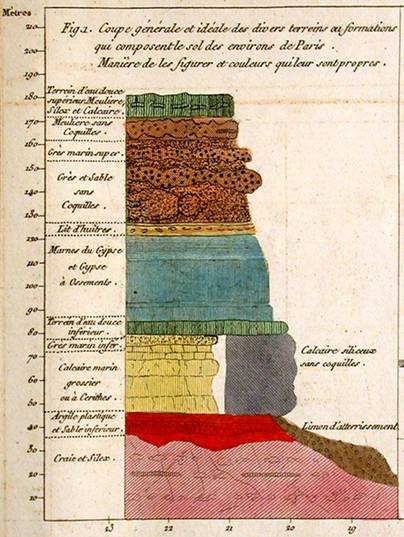

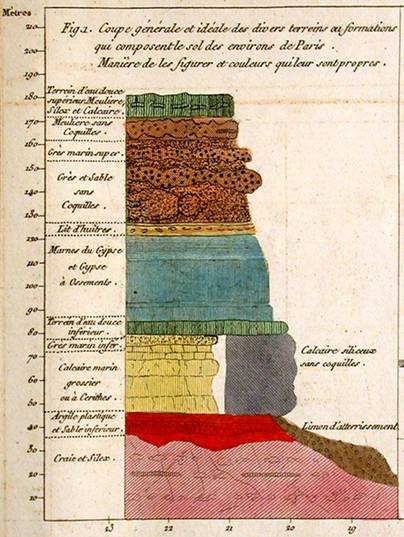

Terrestrial and marine rocks

were commonly seen to alternate with each other, and geologists in the early 1800s

felt justified in believing that the layers in the bedrock contained evidence of many such

watery catastrophes (“debacles”) through time: so the idea of a final deluge

prior to the establishment of the “present order of things” was not alien to

their thinking: that this deluge might be the Genesis Flood was, for a time, a

happy possibility.

Marine (“marin”) and freshwater (“l’eau douce”) formations in the Paris region

(Cuvier 1811, p.271)

http://earth.unh.edu/Schneer/composite.jpg

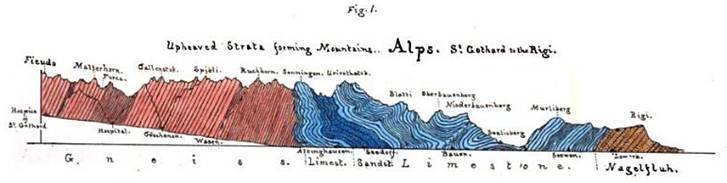

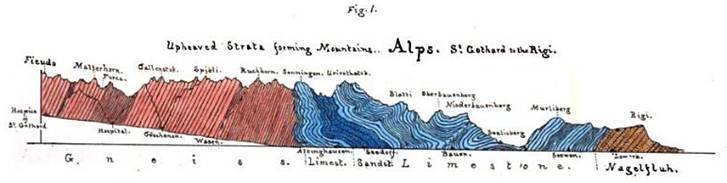

If a series of regional floods

or deluges was responsible for diluvial (drift) deposits and landforms, then the question arose as to

the cause of the flooding. Here, the question of these deposits and landforms

perhaps connected with ideas concerning mountain-building. The majority opinion,

including that of the philosopher William Whewell, was that mountain building

was a rapid process of an intensity that was unknown today: the primary evidence

of this lay in the extensive, high-altitude "convulsed strata" that were well

documented in numerous studies of The Alps and other mountain ranges. Possibly

uplift was sufficiently rapid as to generate huge inundating waves along with melting of

mountain glaciers: the latter could generate a flotilla of ice-bergs that might

carry off huge boulders into distant parts.

"Upheaved strata forming mountains . . Alps. St.

Gothard to the right."

(de la Beche 1830)

Other geologists, such as

Charles Lyell, did not doubt that land and sea had interchanged frequently,

though less dramatically. He was disposed to see a greater uniformity in the workings of

the planet -- or, at least, worked hard to interpret the rock record in these

terms: hence the subtitle of Lyell’s “Principles of Geology” -- “Being an

attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth's surface, by reference to

causes now in operation.” To someone like Lyell, a strict uniformitarian, the idea of full-blown, lowland,

continental glaciation was suspiciously “catastrophic” -- certainly out of the

ordinary as he saw the workings of the planet.

|

|

|

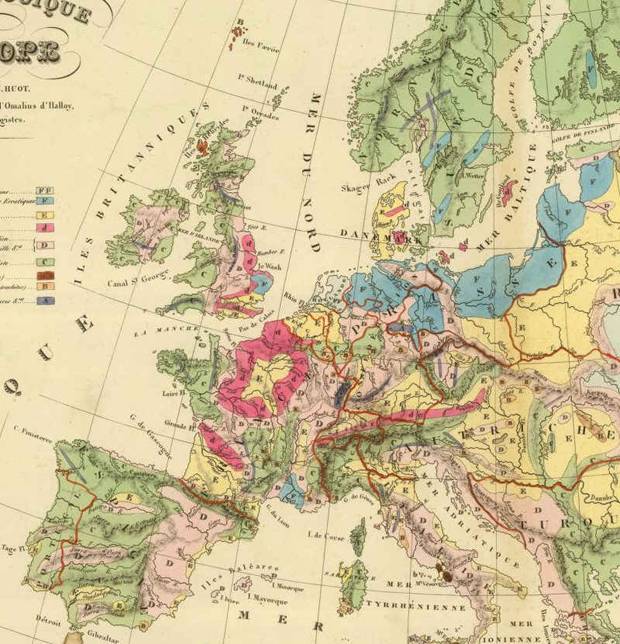

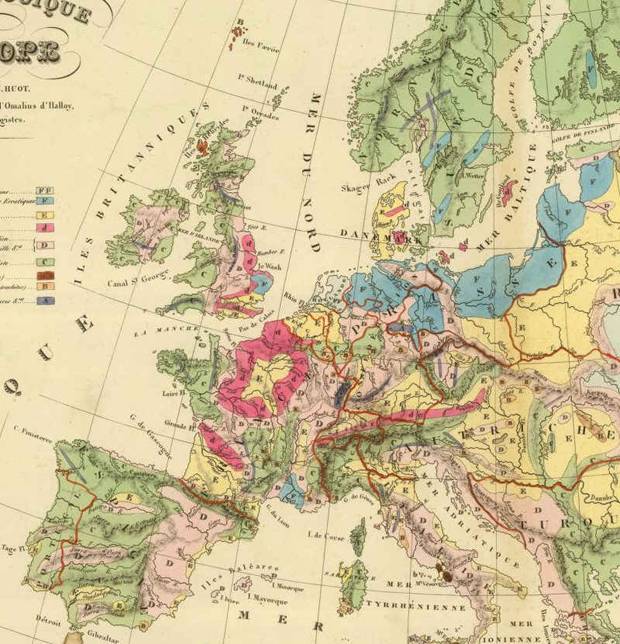

Boue’s

“Carte geologique de l’Europe” of 1831.

http://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~34596~1180208:Carte-Geologique-d-Europe--Dressee-?sort=Pub_Date%2CPub_List_No_InitialSort

-

Blue (“Terrain diluvien” – “Blocs erratiques”) and

Yellow (“Terrain Tertiare”) : regions known to have been submerged at various times during the last

geologic epoch.

-

Red (“Terrain Secondaire”

- chalk) and Pink

(“Terrain Secondaire” - coal, red

sandstone, and limestone) : regions also accepted as

largely water-laid, at an earlier time.

-

Green

represents “Terrain Primaire,” and there are also small areas of

“Terrain Volcanique” and “Terrain Plutonique.”

Lyell used a

simplified version of Boue’s map in his 1833 edition of “The

principles of geology” (volume 2) to illustrate the areas of

Tertiary (and Quaternary) transgressions. As Boue’s map implies, the

idea of a universal flood was becoming superseded by the idea that the sea

had invaded different, limited regions at different times (see

Rudwick 2009). |

Roderick Murchison, a colleague of Lyell, was a strong

proponent of the action of water on the land. To him, the "glacier theory" as extended

beyond the Alps was "beyond the bounds of legitimate induction" and constituted

a "doctrine" that might, he feared, "take too strong a hold on the mind."

However, in 1842, he could point to the fact that "the greater number of

practical geologists of Europe are opposed to the wide extension of a

terrestrial glacial theory" and "the greatest geological authorities on the

continent, led on by Von Buch who has so long studied these phaenomena in his

native land, are opponents to the views."

Therefore, by 1840 geologists

had several theories that made sense of surface features they all recognized --

no one disputed what an erratic was, or that striations and roches moutonnees

generally lined up in the same direction within the same region, or that boulder

clay was an unusually unsorted material, etc. – but how all these were

understood to have been formed was subject to debate that did not at first

include glaciation. When glaciation was suggested, even on a limited regional

scale in the Alps, no one in either camp (catastrophist or uniformitarian) found it easy to accommodate it within

their frame of thinking. The rock record that was best known at the time (the

Tertiary) was limited and, while it undisputedly contained abundant evidence of

the action of water across the European landmass, there was nothing to suggest

the direct action of glacial ice (although the seas that covered the land at

various times might bring in ice bergs). In fact, if anything, fossil evidence

suggested that climate had been warmer (not glacial) in the geologic past.

But regardless of what the

majority believed, change was beginning to happen. In 1841(b) Edward Hitchcock, the first President of the

Association of American Geologists, speculatively applied the glacial theory to "flood" features

in North America and noted: "I seemed to be acquiring a new geological sense;

and I look upon our . . . ensemble of diluvial [flood] phenomena,

with new eyes."

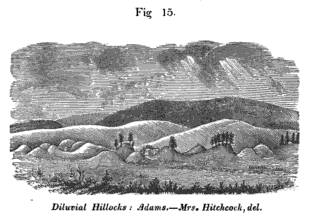

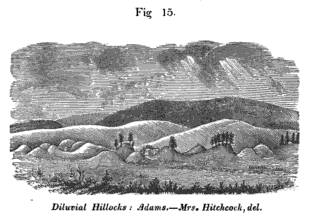

"Diluvial Hillocks: Adams" (MA: Hitchcock

1841a)

In a report on the geology of Massachusetts, Hitchcock

initially interpreted several features as "Diluvial Hillocks . . which are

really the work of water: having been unquestionably produced by that diluvial

agency which has essentially modified this whole region." And he also interpreted

several features on Mount Monadnoc (roches moutonees, striations, etc.) as being diluvial. However, prior to the final publication of the report he inserted

a "Postscript: Glacio-aqueous Action between the Tertiary and Historic Periods,

denominated in my Report, Diluvial Action." In this postscript, he reviewed the

recently-proposed glacial theory and re-interpreted the hillocks as glacial

moraines, and the features on Mount Monadnoc as being similar to features

reported in the Alps by proponents of the new glacial theory "which is is now

exciting a great interest in Europe" -- even although, as he admitted, "In a

country like ours . . no glaciers exist except in very high latitudes." He

concluded, without foreclosing debate: "the theory of glacial action has imparted a fresh and a lively

interest to the diluvial phenomena of this country. It certainly explains most

of those phenomena in a satisfactory manner."

If a glacial theory was to be

accepted, then existing ideas about processes, climate, and the nature of

environmental change would have to be revised or rejected -- or, "looked upon .

. . with new eyes."

REFERENCES

Agassiz, L. 1837

Discours prononce a l’ouverture des seances Société Helvétique des Sciences

Naturelles, a Neuchatel le 24 Juillet 1837. Actes de la Société

Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, réunie à Neuchâtel, p. v-xxxii

http://books.google.com/books?id=e_taAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR5 [Opening

remarks by the President of the Society: “The discourse of Neuchatel”]

ENGLISH TRANSLATION: Upon Glaciers, Moraines, and Erratic Blocks; being the

Address delivered at the opening of the Helvetic Natural History Society, at

Neuchatel, on the 24th of July 1837, by its President, M. L. Agassiz. The

Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal v.24 (Oct. 1837-April 1838) p.364-383

http://books.google.com/books?id=2yEAAAAAMAAJ&dq=Agassiz%20Edinburgh&pg=PA364

Berger, W.H. 2007 On the

discovery of the ice age: science and myth. pp. 271-278 in L. Piccardi

and W.B. Masse (eds.) Myth and geology Geological Society of London, Special

Publication 273 GSL, London

http://www.google.com/books?id=F7pZfLUoHJIC

Buckland, W. 1820 Vindiciæ

geologicæ; or The connexion of geology with religion explained, in an inaugural

lecture delivered before University of Oxford, May 15, 1819, on the endowment of

readership in geology (William Buckland Publisher, Oxford)

http://www.uwmc.uwc.edu/geography/Buckland/Vindiciae

Geologicae William Buckland.pdf

Charpentier, J.

de 1841 Essai sur les glaciers et sur le terrain erratique du bassin du Rhone

(Marc Ducloux, Laussane)

http://books.google.com/books?id=eGwsSDuzkSAC&pg=PP7

Collomb, E. 1847

Preuves de l'existence d'anciens glaciers dans les vallées des Vosges (Victor

Masson, Paris)

http://books.google.com/books?id=8usTAAAAQAAJ

http://jubil.upmc.fr/sdx/pl/doc-tdm.xsp?id=GR_000363_001_d0e35&fmt=upmc&base=fa&root=&n=&qid=&ss=&as=&ai=

Cuvier, G. ,

Brongniart, A. 1811 Essai sur la Géographie Minéralogique des Environs de Paris

http://books.google.com/books?id=HQQTAAAAMAAJ&pg=PP7

de la Beche, H.T. 1830 Sections and

views illustrative of geological phenomena. (Treuttel & Wurtz, London)http://books.google.com/books?id=6DQAAAAAQAAJ&pg=PT16#v

Figuier, L. 1863 The world

before the deluge (Cassel, Petter, Galpin & Co., London)

http://imgbase-scd-ulp.u-strasbg.fr/displayimage.php?album=963&pos=3

http://www.geology.19thcenturyscience.org/books/1872-Figuier-BeforeFlood/htm/doc.html

Hitchcock, E., 1841a Final report

on the geology of Massachusetts: Vol. I. containing I. Economical geology. II.

Scenographical geology. (J.H. Butler, Northamption MA)

http://books.google.com/books?id=sTcAAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR1#v

Hitchcock, E., 1841b First

anniversary address before the Association of American Geologists at their

Second Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, April 5, 1841. (B.L. Hamlen, New Haven).

http://www.google.com/books?id=ErkQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA1#v

Lyell, C.

1833 Principles of geology, volume 2 (John Murray, London)

http://www.google.com/books?id=JoW8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PR1#v

Lugg, A. 1978 Overdetermined

problems in science. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science v.9(1)

p.1-18

Murchison, R.I. 1842 President's

Anniversary Address 1842: The glacial theory. Proceedings of The Geological

Society of London v.III (Nov. 1838- Jun. 1842) part II (1842) no.86 p.671-687

http://www.google.com/books?id=giPPAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA671

Rudwick, M.J.S. 2009 Biblical

flood and geological deluge: the amicable dissociation of geology and genesis.

p.103-110 in M. Kolbl-Ebert (ed.) Geology and religion: A history of

harmony and hostility. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 310

(Geological Society, London)

http://books.google.com/books?id=w1NUHmio_jEC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v

Sefstrom, N.G.

1836 [pub.1838] Undersökning af de räfflor, hvaraf Skandinaviens berg äro med

bestämd riktning fårade, samt om deras sannolika uppkomst. Kongliga Vetenskaps

Academiens handlingar, for the year 1836 p.141-227 [An investigation of the

furrows which traverse the Scandinavian Mountains in certain directions,

together with the probable cause of their origin.]

http://books.google.com/books?id=Q7g4AAAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA41

FULL ENGLISH

TRANSLATION: Sefstrom (Nils Gabriel). An investigation of the furrows which

traverse the Scandinavian mountains in certain directions, together with the

probable cause of their origin. S. H. Thomas (trans.) p.81-144, 382 (map) in

R. Taylor (ed.) 1843 Scientific memoirs v.3 part 9 (R & J. E.Taylor, London)

http://books.google.com/books?id=qsY-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA82#v

Unger, F. 1851 Ideal Views of

the Primitive World, in its Geological and Palaeontological Phases (Taylor and

Francis, London)

Whewell, W. 1831 Review of volume 1 of Lyell's "Principles

of geology." The British Critic, Quarterly Review, and Ecclesiastical Record

v.9, p.180-206

http://www.archive.org/details/britishcriticqua09londuoft

<<--

Project Home | 2. GoogleEarth Tour

-->>

![[Deluge+of+the+North+of+Europe.jpg]](INTRODUCTION_files/image002.jpg)