|

BRITAIN IN THE 1830s

"The

Fighting Temeraire, tugged to her Last Berth to be broken up, 1838."

J.M.W. Turner.

Although

you would not know it from accounts of the Geological Society of London,

Britain in the 1830s was a society in economic, social, and political

transition. Britain was becoming increasingly industrial and urban, with

growing middle and working classes, and a corresponding decline in the power of

the conservative rural, landed class: the world of Dickens was replacing the

world of Jane Austin, but science remained a gentlemanly pursuit. While Britain

had lost its American colonies (but not Canada) its colonial power overseas was

increasing in the Indian sub-continent and in Australia, and it was becoming

increasingly aggressive in its approach to China. The technological potential

of science was beginning to be fully realized in industry, and social and

legislative change was prompted by societal shifts the new economy engendered.

Science and scientific advances was a popular subject in magazines and

newspapers and the British Association for the Advancement of Science, founded

in 1831 (and parodied by Dickens in The Mudfrog Papers, 1837-38), represented a

desire to engage the public in matters of science and to increase the presence

of science outside of London. Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology was the

first text to present an account of advances in geology to the general public.

Some acclaimed the "decline of British science" at this time while

others, such as Coleridge, criticized its growing influence on the life of the

country. Carlyle asserted that The Romantic Age was giving way to The Age of

Machinery: "The Progress of Science . . . is to destroy Wonder."

|

|

TRENDS AND EVENTS

Population in England is rising quickly,

although increasing emigration to the America slows this. In 1835 the doctrine

of “terra nullius” prepares the way for increased settlement in Australia.

|

|

Thomas Robert Malthus dies in 1834. The

six editions of his Principles of Population focused on population growth among

the different classes in England; he argued against laws aimed at alleviated

poverty, arguing that they would only result in further growth. Thomas Robert Malthus dies in 1834. The

six editions of his Principles of Population focused on population growth among

the different classes in England; he argued against laws aimed at alleviated

poverty, arguing that they would only result in further growth.

|

|

Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, presenting

contrasting views of society at this time, are published in the mid-late 1830s.

Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, presenting

contrasting views of society at this time, are published in the mid-late 1830s.

|

|

December 27, 1831, Charles Darwin sails

from Plymouth as naturalist on the HMS Beagle; he will return to Falmouth on

October 2, 1836. Best known for the biological completed, Darwin also brought

back geological observations that contributed a great deal to contemporary

geological debates. December 27, 1831, Charles Darwin sails

from Plymouth as naturalist on the HMS Beagle; he will return to Falmouth on

October 2, 1836. Best known for the biological completed, Darwin also brought

back geological observations that contributed a great deal to contemporary

geological debates.

|

|

Increasing

industrial growth is shifting population and the power base in England. At the

start of the century 20% of the population lived in cities – by the end of the

century is was over 50%. London and the Midlands see dramatic growth through

the 1830s. The 1832 Reform Act changed radically the electoral system of Great

Britain, redistributing seats in favor of the growing industrial cities. One in

seven men now had the vote.

Growing pains

of urban-industrial society were first addressed in 1833 Shaftesbury's Factory

Act, which limited the hours of children's employment, and 1834 saw the first

Inspected Factory Act, and the Poor Law Amendment Act introduced a more

efficient administrative structure for the relief of poverty.

|

|

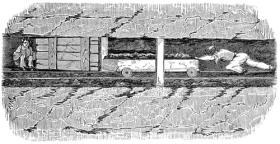

The

Liverpool & Manchester Railway opened on 15 September 1830 – the first

intercity railway in the world. Conceived and constructed by George Stephenson,

the line was a great feat of engineering, using viaducts, tunnels and cuts to

connect these two growing industrial cities. The

Liverpool & Manchester Railway opened on 15 September 1830 – the first

intercity railway in the world. Conceived and constructed by George Stephenson,

the line was a great feat of engineering, using viaducts, tunnels and cuts to

connect these two growing industrial cities.

|

|

At the

opening day ceremony William Huskisson,

a popular member of Parliament for

Liverpool, misjudged the speed of the approaching train and was run

over, becoming the world's first railway passenger fatality. At the

opening day ceremony William Huskisson,

a popular member of Parliament for

Liverpool, misjudged the speed of the approaching train and was run

over, becoming the world's first railway passenger fatality.

|

|

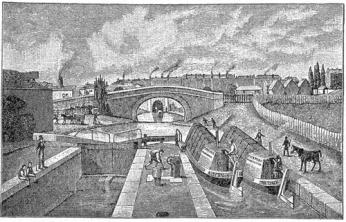

By 1836 the first canals are being

bought by railway companies for rights of way – the end of the great canal era

are in sight. In 1838 the London Birmingham railway

starts, connecting London to the Midlands. [Euston Station, London, 1837] By 1836 the first canals are being

bought by railway companies for rights of way – the end of the great canal era

are in sight. In 1838 the London Birmingham railway

starts, connecting London to the Midlands. [Euston Station, London, 1837]

|

|

Map of

railways running into London from the south and west, ca. 1840.

|

|

1833 Abolition of Slavery Act – Britain abolishes slavery

and provides for the emancipation of enslaved people in the British West

Indies, to take effect in August 1834. The Act declares that the former

enslaved people must serve a period of apprenticeship before receiving full

emancipation. Originally this period was set at six years, but it was later

reduced to four. 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act – Britain abolishes slavery

and provides for the emancipation of enslaved people in the British West

Indies, to take effect in August 1834. The Act declares that the former

enslaved people must serve a period of apprenticeship before receiving full

emancipation. Originally this period was set at six years, but it was later

reduced to four.

|

|

Queen

Victoria, aged 18, is crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 28, 1838: the

Victorian Age begins. Queen Victoria’s reign that will last 64 years.

|

|

1838: The Chartist movement begins, demanding

representative government and universal suffrage – going well beyond the modest

reforms introduced in 1832: it is seen as a radical, working class labor

movement. 1838: The Chartist movement begins, demanding

representative government and universal suffrage – going well beyond the modest

reforms introduced in 1832: it is seen as a radical, working class labor

movement.

|

|

1839: The first Opium War begins: Britain acts to force

the government of China to permit trade in opium. 1839: The first Opium War begins: Britain acts to force

the government of China to permit trade in opium.

|

|

SCIENCE ORGANIZATIONS

The British Association for the

Advancement of Science is founded in 1831. William Whewell coins the term

"scientist" which is used at the BAAS meeting of 1834 for the first

time, eventually replacing "natural philosopher" and "men of

science." The British Association for the

Advancement of Science is founded in 1831. William Whewell coins the term

"scientist" which is used at the BAAS meeting of 1834 for the first

time, eventually replacing "natural philosopher" and "men of

science."

1835: The

British Geological Survey is organized under of Britain under Henry T. de la

Beche.

1835: The

British Geological Survey is organized under of Britain under Henry T. de la

Beche.

|

|

WOMEN IN GEOLOGY

Geology was, in some sense, a “field sport.” Reading through accounts of field work, one is struck by the distances travelled in coaches (e.g. Agassiz's work in Scotland in just two weeks) and the ground covered in hikes to reach sites. At the time this was not seen as an activity suitable for women, but there were women active in science at the time (perhaps most notably Caroline Herschel, the astronomer). In geology, Mary Anning (1799-1847) (at right) made a living finding and selling fossils in the Lyme Regis area, and her reputation was such that she was eulogized upon her death in the Presidential Address of de la Beche along with Alexandre de Broingniart: "there are those among us in this room who know well how to appreciate the skill she employed, (from her knowledge of the various works as they appeared on the subject,) in developing the remains of the many fine skeletons of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, which without her care would never have been presented to comparative anatomists in the uninjured form so desirable for their examination" (de la Beche, 1848, p.xxv). Geology was, in some sense, a “field sport.” Reading through accounts of field work, one is struck by the distances travelled in coaches (e.g. Agassiz's work in Scotland in just two weeks) and the ground covered in hikes to reach sites. At the time this was not seen as an activity suitable for women, but there were women active in science at the time (perhaps most notably Caroline Herschel, the astronomer). In geology, Mary Anning (1799-1847) (at right) made a living finding and selling fossils in the Lyme Regis area, and her reputation was such that she was eulogized upon her death in the Presidential Address of de la Beche along with Alexandre de Broingniart: "there are those among us in this room who know well how to appreciate the skill she employed, (from her knowledge of the various works as they appeared on the subject,) in developing the remains of the many fine skeletons of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, which without her care would never have been presented to comparative anatomists in the uninjured form so desirable for their examination" (de la Beche, 1848, p.xxv).

Mary Morland, who became William Buckland's wife in 1825, frequently accompanied him as an assistant, and was an expert at sketching specimens, including some of his most famous of the Megalosaurus bucklandii. More commonly, women were seen as providing "encouragement" to their gentleman-husbands, something that fit both their status.

For more information, see:

- Creese, Mary R.S. and Crease, Thomas M. 1994. "British Women who Contributed to Research in the Geological Sciences in the Nineteenth Century," British Journal of the History of Science 27, 23-54.

- De la Beche, H.T. 1848 Presidential Address. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, v.4(1), p.xxi-xxv. http://books.google.com/books?id=puAGAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR21#v

- Emling, S. 2009. "The fossil hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution and the Woman Whose Discoveries Changed the World." London, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Turner, S. 2009 Not so quiet persuasion: the canon of women in the geological sciences. Metascience v. 18(3), p.405–412.

- Burek, C.V. Higgs, B. (eds), 2007. "The Role of Women in the History of Geology." London, The Geological Society, Special Publication 281.

|

SCIENTISTS (OTHER THAN GEOLOGISTS)

The 1820s has

seen the deaths of Joseph Banks (1820), William Herschel (1822), and Humphry

Davy (1829): a new generation of science leaders is beginning to emerge.

|

David Brewster

|

Charles Babbage

|

John Dalton

|

|

Michael Farraday

|

John Herschel

|

Mary Sommerville

|

|

|

CRITICS AND PHILOSOPHERS OF SCIENCE

|

Samuel

Taylor Coleridge

|

William

Whewell

|

|

|