| Debating Glacial Theory, 1800-1870 – Epilog, Part 2 |

| Home || Debate Profile || Epilog, Pt.1 || Epilog, Pt.3 | |

The "controversy" over

the glacial theory rumbled on through the 1860s, as these two contrasting images

from the 1850s and 60s attest to:

Lyell and Darwin never

fully reconciled themselves to the new theory (e.g. Darwin 1855) but Murchison, above all, carried on the fight actively: "Until lately geologists seemed to be generally agreed

that most of the numerous deep openings and depressions which exist in all lofty

mountains were primarily due to cracks, rents, and denudations, which took place

during the various movements which each chain had undergone at various periods.

These apertures, it was supposed, were necessarily enlarged by long diurnal

atmospheric agency and the action of torrents carrying down boulders and

detritus; such action being most intense in those mountains where snows and

glaciers prevailed, the melting of which necessarily produced great debacles. In

the place of this modus operandi, another theory has been applied to all

those mountains, which, like the Alps, have been for long periods the seat of

glaciers." "I have had strong doubts as to whether the great blocks

derived from Mont Blanc, and which lie on the slopes of the Jura, were ever

borne thither by a vast solid glacier which advanced from the Lake of Geneva

over the Cantons of Vaud and Neufchatel. Whilst fully believing in the great

power of glaciers and their agency, my opinion was that these blocks were rather

transported to their present habitats on the Jura on ice-rafts, which were

floated away in water to the N.N.W.,

when the great glaciers melted, and the low countries were flooded. . . .

there is still in it nothing which supports the opinion, as indeed Sir Charles

has himself observed, that the deep cavity in which the lake lies [Lake Geneva]

was excavated by ice." Murchison even argued that ice could not flow into the

Lake Geneva basin, but would flow across it as a bridge.

Nevertheless, the

older paradigms of "Diluvium" and "Drift" were spent -- they had

nothing new

to offer and the glacial paradigm, steered now by a younger generation, rolled on,

incorporating new and more varied facts. If Murchison had thought that "the

glacier theory" was speculative and lacking in inductive observation, the tables

were completely turned on him in the 1860s. Thomas Francis Jamieson (1829-1913)

revisited the Parallel Road of Glen Roy and effectively

disposed of Darwin's "marine submergence" theory using a variety of evidence,

primarily of a positive nature. Of particular importance was his finding of

moraines as barriers in several instances, recognizing that deposition into

water had modified them. "The absence, therefore, of any good positive evidence

in favour of the marine theory, and so many considerations urging themselves

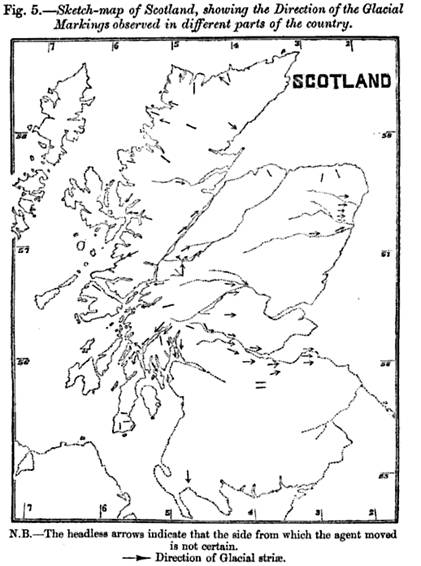

against it, seemed to me to render it untenable." His paper on the "ice-worn" rocks of Scotland is a

classic observation and reasoning. He described a major flood in 1859 that had

no impact on bedrock and failed to erase in any way striations that pre-dated

the flood. In addition the material left behind was well-sorted (the finer

material having been carried away). Regarding the ice-berg drift theory of striations and

erratics, he wondered why interior valleys and slopes are just as striated and

grooved as coastal valleys. Plus, sources of rock show they moved towards the

sea rather than inland. "But the instances I have mentioned above, being all

purposely taken from localities close upon the present shores of Scotland, in my

opinion go to prove that even in the low grounds this glacial erosion has

radiated from the interior; and that not only in the mountain-glens has this

action been due to glaciers, but down to the present coast-line we must still

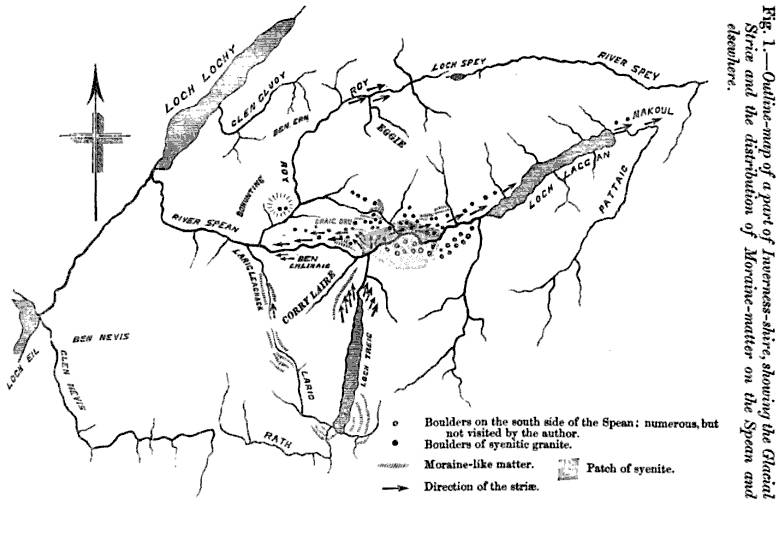

ascribe it to an agent moving off the land, and not to sea-ice." Jamieson's (1862) map showing the

direction of striae outwards towards the coast. In addition he pointed to observations on icebergs from

Greenland that showed icebergs milling around in different directions with

near-shore currents -- which would give no clear direction to striae

(also, for example, see iceberg scours in the "Glen Roy Revisited" Episode). And the new theory was applied to the origin of

"glacial" valleys: "Now I think the amount of rock which has been worn away,

even at the mouths of the sea-lochs of the W. Highlands, as at Loch Fyne

and at the Kyles of Bute, opposite the steamboat-quay at Colintrive, by the

glacial action, is far too great to be accounted for by the passage of even a

succession of such debacles. The rounded outlines of the tough gneiss and

syenite, which I there saw, denoted to my mind the long-continued grinding

action of ice slowly moving over them ; for I think the rapid, hurried rush of a

sludgy mass, even although repeated, would not produce such finely rounded

contours: neither would the grooves and furrows be so persistent and rectilinear

in their direction ; for the ice being in broken masses, and accompanied with

water and melting snow, would have more freedom of movement than the rigid mass

of a huge glacier or ice-stream filling the valley; and in the lower open

grounds, where there were no heights to confine the torrent, the straight

persistent direction of the scores is even more striking than in the glens and

gorges, and to my mind still more inexplicable by such a catastrophe or series

of catastrophes." Jamieson's (1862) map showing a Loch

Treig glacier moving syenite from a source in both directions and up a slope,

something he believed impossible by sea ice. Sir Andrew Crombie Ramsay (1814-1891)

provided a detailed account of how lake basins, such as Lake Geneva, might

be formed by glacial action, showing quite specifically that they were not

associated with structural features or faults or any other "cracks or rents"

(Murchison). When Murchison gave an address to the Royal Geographical Society

"On the relative

powers of glaciers and floating icebergs in modifying the surface of the earth,"

Ramsay (1864) fumed in response against what he saw an an ad hominen

attack: "I must needs be wrong because

they are so eminent [geologists cited by Murchison]. . . . Assertions and crude

ideas in all kinds of books and papers are "as plenty as blackberries; " but for

clear demonstrations—none are given. . . . Unless I were to write a

special elementary treatise on denudation, enough has now been said to show that

the theory of formation of great systems of valleys by erosion in which water

and ice are main agents, is not a mere absurdity, and I do not therefore care

minutely to analyze the assertions that many of the Alpine rivers flow in

fissures or deep chasms,.. . which water alone never could have opened out; or

again, that the Rhine and the Danube never could have eroded those deep abrupt

gorges through which they here and there flow, and which are manifestly due to

original ruptures of the rocks." Although Ramsay viewed Murchison as a respected

senior colleague and friend, he saw his reasoning as

deficient, if not non-existent. James D. Forbes went on to establish

more fully the science of glaciology. He developed a theory of viscous flow of

glaciers and became embroiled in a dispute primarily involving priority over

ideas. This dispute involved the physicist John Tyndall (1820-1893), who

promoted a theory of regelation (melting and re-freezing – giving the appearance

of flow) and Louis Agassiz. This was a very public dispute. Nevertheless,

progress was made on a basic subject (i.e. how ice flows and under what

conditions of terrain and slope) that had hindered acceptance of the theory

overall.

Croll also worked on the theory

of ice flow but in a paper in 1870 Croll

contributed another, crucial piece of the puzzle: in a study on

"boulder-clay" (drift) in northern Scotland he showed that "The shells which the

Boulder-clay of Caithness contains have . . . evidently been pushed out of the

bed of the North Sea by the land ice which formed the clay itself." This was

important because the existence of marine shells had been used to support the

iceberg drift theory and continued to support Lyell and Darwin in their belief

of lowland iceberg drift. By identifying species, Croll was able to argue that

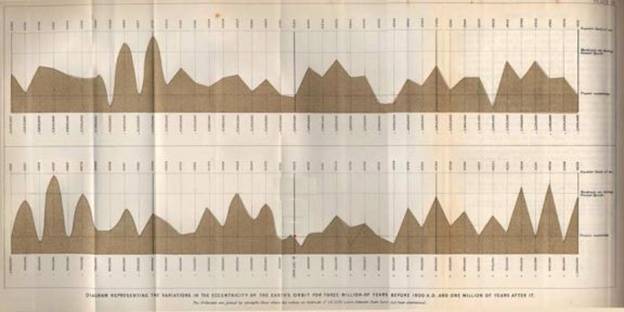

the species were not Arctic but were native to mid-latitudes and had pre-dated the coming of the ice. Variations in the

earth’s orbit over four million years (1 million after 1800) James Geikie (1839-1915) was

also one of the new generation and his "The Great Ice Age and its relation to

the antiquity of Man" sums up much of the new the new work and stands in

opposition to Lyell's work at this time which still referred to the lowland

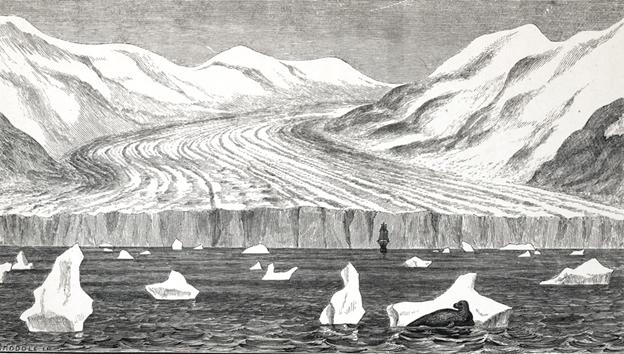

ice-berg drift theory. Increasingly, in all of this work, new observations from

Greenland and Antarctica were used to corroborate elements of the theory as

applied to Scotland and elsewhere.

Glacial scene of Northern Greenland Finally, in same year as Ramsay and

Jamieson were publishing their great papers on glacial action, Joseph Beete Jukes (1811-1869)

also solved another piece of the puzzle: he showed how rivers can cut across

regional rock structure through the mechanism of "superimposing" drainage --

that over time rivers can flow across an area on younger, horizontal rocks

and then be let down upon older folded or tilted strata. Thus thus

rivers like the Rhone can come to flow through complex structures, such as folds. It should be noted, that Jamieson,

Ramsay, Forbes, Croll, and Geikie were all Scottish – their interest in glaciers

and glaciation having been piqued by Agassiz’s visit and by the challenges posed

in explaining Scottish Highland landscapes. Thus, to some extent, the

locus of work moved from central Europe to NW Europe in the final establishment

of the theory of “land ice.” Thus, the "fact" of glaciation, accepted by

all scientists today, emerged slowly between 1835 and the 1870s. First

accepted in the Alps, where there are glaciers, it was then extended to

incorporate phenomena across northern Europe. The older "flood" theory proved

hard to dislodge, especially in lowland areas, as it was well embedded in thinking and there appeared to be

ample evidence to back it up. There were

some individuals who "converted," such as Buckland and Ramsay --

Buckland compromised with his contemporaries, while Ramsay had been an iceberg

drift proponent -- but its

final acceptance was due as much to the passing of generations as anything else.

Its greater explanatory power simply was not accepted by the older generation of

geologists, but by the 1870s it incorporated so many ideas about the physical

landscape, climate, and the workings of the planet in general that it had moved

from speculation to highly probable to virtual certainty.

QUESTION

Agassiz has often been credited with having been the "father" of the glacial

theory, and this attribution has equally often been criticized as inaccurate,

given the contributions of others. How would you assess Agassiz's contribution?

How "modern" was his conception of glaciation?

REFERENCES Croll, J.

1864 On the physical cause of the change of climate during geological epochs.

The London,

Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science v.XXVIII

(4th Series; Jul-Dec 1864) p.121-137.

http://books.google.com/books?id=J1cwAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA121#v Croll, J.

1867 On the

eccentricity of the Earth's orbit, and its physical relations to the glacial

epoch. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of

Science v.XXXIII (4th Series; Jan-Jun 1867) p.119-131.

http://books.google.com/books?id=W1EEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA119#v

Croll, J. 1867 On

the change in the obliquity of the ecliptic, its Influence on the climate of the

Polar Regions and on the level of the sea. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin

Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science v.XXXIII (4th Series; Jan-Jun

1867) p.426-445.

http://books.google.com/books?id=W1EEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA426#v Croll, J.

1870 The boulder-clay of Caithness - a product of land-ice. The Geological

Magazine v.VII (Jan-Dec 1870) p.271-278.

http://books.google.com/books?id=ePVjAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA271#v

Croll, J. 1875

Climate and time and their geological relations: a theory of secular changes of

the Earth's climate (London,

Daldy, Isbister & Co.)

http://books.google.com/books?id=mLYKAQAAIAAJ&pg=PR3#v Darwin, C. 1855 On the

power of icebergs to make rectilinear, uniformly directed grooves across a

submarine undulatory surface. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical

Magazine and Journal of Science v.10 (Jul-Dec) p.96-98 Fleming, J.R. 2006 James

Croll in Context: The Encounter between Climate Dynamics and Geology in the

Second Half of the Nineteenth Century. History of Meteorology, v.3 p.43-53

http://www.meteohistory.org/2006historyofmeteorology3/3fleming_croll.pdf Forbes, J.D. 1845 Travels

through the Alps of Savoy and other parts of the Pennine chain with observations

on the phenomena of glaciers. (Edinburgh, Adams and Charles Black; London,

Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans) Forbes, J.D. 1846

Illustrations of the Viscous Theory of Glacier Motion Part I. Containing

Experiments on the Flow of Plastic Bodies, and Observations on the Phenomena of

Lava . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, v.136,

p.143-155.

http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/136.toc Forbes, J.D. 1846

Illustrations of the Viscous Theory of Glacier Motion Part II. An Attempt to

Establish by Observation the Plasticity of Glacier Ice. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society of London, v.136, p.157-175.

http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/136.toc Forbes, J.D. 1846

Illustrations of the Viscous Theory of Glacier Motion Part III. Geikie, J.

1877 (1874) The Great Ice Age and its relation to the antiquity of Man (D. Appleton

&Co., New York)

http://books.google.com/books?id=zjQaeq03ikIC&pg=PR3 Hamlin, C. 1982

James Geikie, James Croll, and the eventful ice age. Annals of Science v.39,

p.565-583 Hevly, B. 1996 The heroic

science of glacier motion. Osiris v.11, p.66-86 Jamieson, T.F.

1862 On the ice-worn rocks of Scotland. Quarterly Journal of the Geological

Society, London, v.18, p.164-184 Jamieson, T.F.

1863 On the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy,

and their Place in the History of the Glacial Period, Quarterly Journal of the

Geological Society, London v. 19, issue.1-2; p. 235-259 Jukes, J.B.

1862 On the mode of formation of some of the river-valleys in the south of

Ireland. Quarterly Journal, Geological Society, London, v.18, p.378-403

http://books.google.com/books?id=RQQAAAAAMAAJ&pg=RA2-PA378#v

Murchison R.I. 1864 On

the relative powers of glaciers and floating icebergs in modifying the surface

of the earth. From the Address of the President of the Royal Geographical

Society, May 23, 1864. (London, W. Clowes and Sons)

http://books.google.com/books?id=kYs5AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA1#v Ramsay, A.C.

1857 On certain peculiarities of climate during part of the Permian Epoch.

Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain v.2 (1854-1858) p.417-421

http://books.google.com/books?id=LxNcKnmdDTIC&pg=PA417#v Ramsay, A.C.

1858 On the geological causes that have influenced the scenery of Canada and the

north-eastern provinces of Canada. Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great

Britain v.2 (1854-1858) p.522-524

http://books.google.com/books?id=tfkAAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA522#v Ramsay, A.C.

1862 On the glacial origin of certain lakes in Switzerland, the Black Forest,

Great Britain, Sweden, North America, and elsewhere. Quarterly Journal,

Geological Society of London, v.18, p.185-204. Ramsay, A.C.

1864 The physical geology and geography of Great Britain: six lectures to

working men delivered in the Royal School of mines in 1863 (Edward Stanford,

London) http://books.google.com/books?id=NMm7AAAAIAAJ&pg=PR1#v Ramsay, A.C. 1864 On the Erosion of

Valleys and Lakes; a Reply to Sir Roderick Murchison's Anniversary Address to

the Geographical Society. The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical

Magazine of Science, v.XXVIII (July-December 1864) p.293-311.

http://books.google.com/books?id=J1cwAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA293#v Tyndall, J., 1861 The glaciers

of the Alps – being a narrative of excursions and ascents, an account of the

origin and phenomena of glaciers, and an exposition of the physical principles

to which they are related (Boston, Ticknor and Fields) Worsley, P.

2006 The British Geological Survey's glaciological expedition to Arctic Norway

in 1865. Mercian Geologist v.16(4) p.263-275 |

|

![[Deluge+of+the+North+of+Europe.jpg]](Final-outcomes_files/image002.jpg)

Adding to

this work, through the 60s

and 70s,

Adding to

this work, through the 60s

and 70s,